Day of Remembrance of Japanese American Incarceration: The story of Toshi Ito

LOS ANGELES (KABC) -- Communities across the country observed the Day of Remembrance on Wednesday - a day when many take time to reflect.

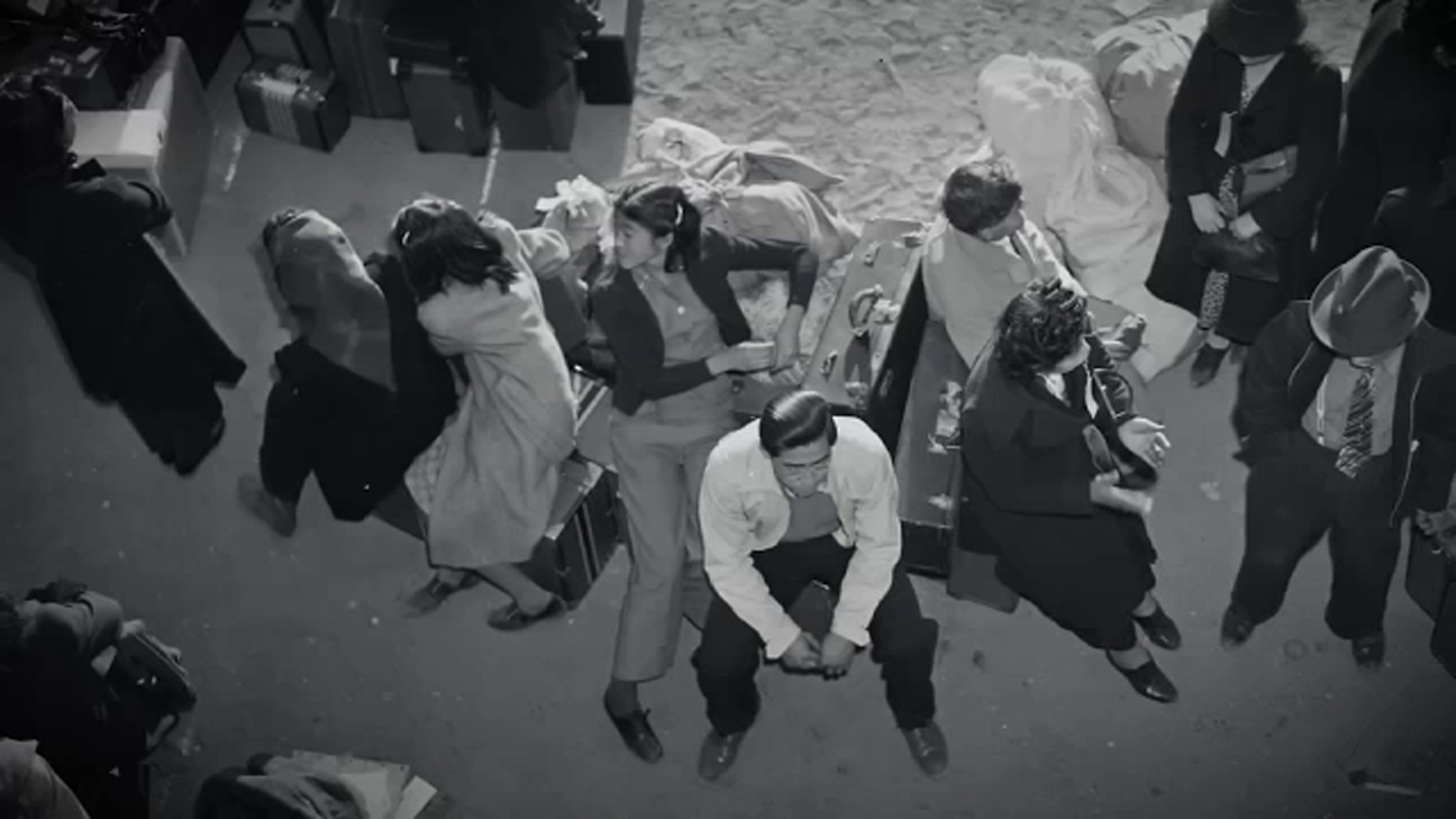

On Feb. 19, 1942, President Franklin D. Roosevelt signed Executive Order 9066, which led to the forced incarceration of more than 120,000 Japanese Americans during World War II.

The executive order has been in the news a lot lately.

Whether good or bad, it provides one person - the President of the United States - incredible power.

A sobering display of that power occurred when Roosevelt stereotyped then violated the rights of a generation of law-abiding American citizens.

Out of my many interviews on the topic, my conversation with Toshi Ito - a dozen years ago - still moves me today.

I first met Ito in 2012.

She walked me around her neighborhood, sat me down in her living room, and showed me photo albums, books, and posters.

She then shared her story about growing up with her mother and father in Los Feliz in a house her father worked hard to get.

"He really loved me, and he took care of me," she said. "He was very successful, and he sold insurance in the Little Tokyo area."

But when World War II broke out, life would never be the same - all because of a simple signature from just one man. Executive Order 9066 led to the mass incarceration of Japanese Americans on the West Coast.

Even though the country was also at war with Italy and Germany, only people of Japanese descent were deemed a threat to national security.

Ito recalls being 17 when 120,000 innocent people were rounded up.

"We got on a World War I vintage train. It was so old and so packed down, it was just rock hard. It was very uncomfortable," she recalled. "It was three days and two nights on that train."

She ended up on a barren prairie at Heart Mountain, Wyoming.

"We arrived in a sandstorm," Ito recalled. "Dirt and sand was just flying all around."

What would follow was three years of humiliation. People crammed in barracks, forced to use public restrooms with no partitions or privacy.

The food was terrible, not to mention the barbed wire and machine guns pointing at them. It was a prison.

But for Ito and many others, the worst part - the part that few talk about - was life after these camps, and the hate they received when they returned home at the end of the war.

"When my mother came back, everybody in the neighborhood knew she was Japanese, so the grocery store and the drug store and all the stores in our neighborhood, they wouldn't sell us anything," said Ito. "So my mother had to take a bus and a streetcar and go near Chinatown to Grand Central Market in Los Angeles and hopefully pass as a Chinese woman to buy our groceries."

The vitriol was constant. Simply pulling the car out of the driveway was heartbreaking as their tires were punctured.

"The neighbors up the street had put tacks on the driveway and put up a sign, 'No Japs,'" said Ito.

But the worst part was the terrible pressure on Ito's father.

"He tried to get a job, and the insurance company wouldn't reinstate his license or, you know, rehire him," she said. "He tried doing physical labor, he tried doing gardening, but he just couldn't do it. We had to sell our Buick, and all his office equipment, his steel cabinets, his typewriters and adding machines and so on."

Until there was only one thing of value he had left: a life insurance policy.

"So ... he committed suicide," said Ito as she held back tears. "I was on my honeymoon. I got a phone call telling me that my father was very ill and that I had to come home to see him. My mother was waiting for me in the car at Union Station in L.A., and that's how I found out."

"I just started to cry, and I went to my mother and I hugged her and I said, 'I'm so sorry,' and then when I got home, I went to his bed on the side he slept, and I just laid there and I cried. I could smell his hair tonic that he wore, and I never cried so much in my life."

Ito and her new husband Jim went on to live a long life together. They had two children, Krislyn and Lance.

Today, we know her son as the honorable Lance Ito, the judge in one of the biggest trials in American History: the murder trial OJ Simpson.

"The internment experience that my parents and grandparents went through does impact my life today," said Judge Ito.

If there is anyone who understands 9066's blatant violation of our constitutional rights, it's Judge Ito.

"The fact that you could take a whole group of people, identified only by national origin, and without any trials, without any procedural safeguards, without due process of law, order them from their homes, order them held against their will, rip them out of their family lives, rip them out of their professional lives, and hold them in a very desolate place for an indefinite period of time, without any judge, saying that this is something that this individual deserves to have happened to them," he said. "It's a violation of due process of law. It's a violation of your right to have a trial. It's a violation of so much of our Constitution. That's the sort of thing that can happen if we're not paying attention, and we need to pay attention every day to maintaining the rights that we have as American citizens ... and that somebody needs to stand up when those rights are violated."

Toshi Ito died in 2018 and Judge Ito has since retired.

The Ito family gives us a powerful lesson as relevant today as it was 83 years ago.

By the way, it was 80 years ago that Japanese Americans began being released from these camps, given $25 and told to go home - often to a home that no longer existed.