Voter turnout for Black citizens is among highest across racial groups, but gaps remain

Experts say systemic issues, poor messaging and accountability problems are some of the reasons disparities persist.

LOS ANGELES (KABC) -- LaTosha Brown is the founder of the nonprofit group Black Voters Matter, an organization dedicated to increasing voter registration and power in Black communities.

Brown said she remembers going to vote with her grandmother, who would "take out her good pocketbook" on Election Day.

"There is a history, a long history, and legacy of Black people using their agency to go vote. It wasn't just a transaction for us," she said.

Brown and other experts say there's a misconception that Black citizens don't vote.

"That's completely not true," according to Dr. Rashawn Ray, a senior fellow at the Brookings Institution.

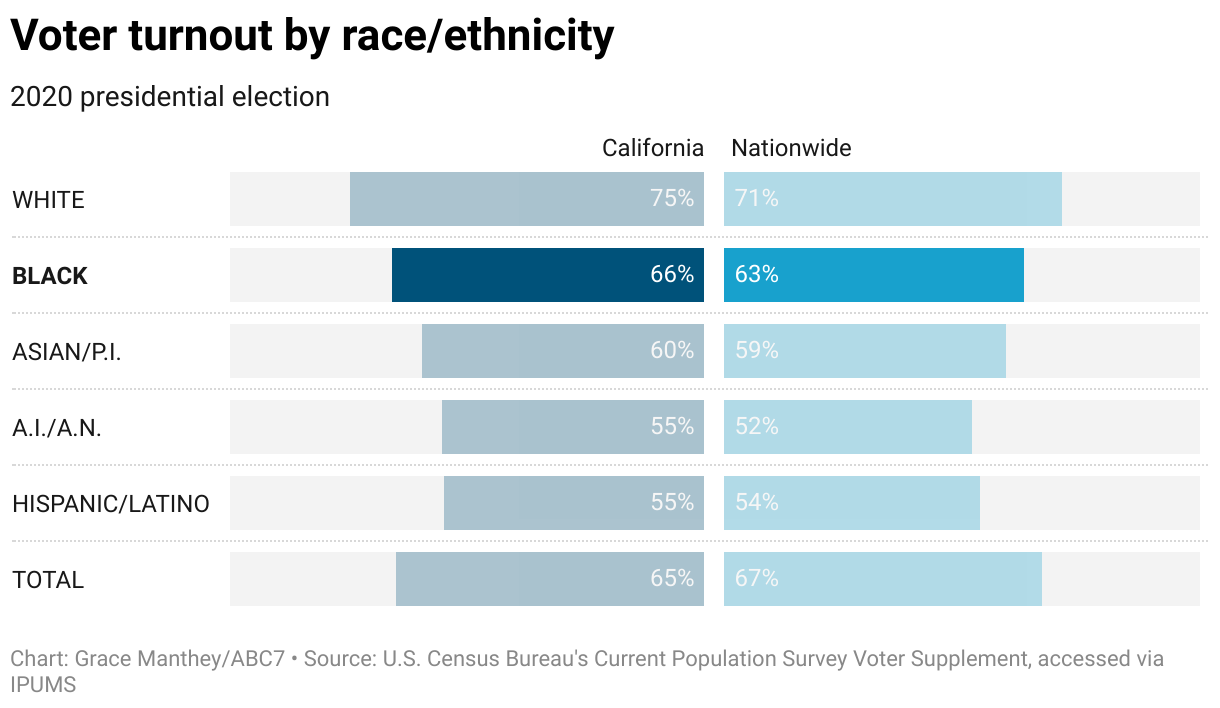

Census survey data shows turnout among Black citizens is the second highest both nationwide and in California.

Ray said many blame Black voters when certain Democratic or Black candidates lose elections, making Black voters "an easy scapegoat."

"But when you look at how long they're waiting, all of the things that they go through to try to put their ballot in, what we actually see is that in some regards, Black people might actually be more committed," Ray said.

Systemic barriers: Jumping through hoops

There is a growing body of research pointing to barriers experienced by people of color when it comes to voting.

A National Bureau of Economic Research study used cell phone data to find that residents in Black neighborhoods stood in line 29% longer and were about 74% more likely to spend more than 30 minutes at their polling place than those in white neighborhoods.

According to one of the authors, Dr. Kareem Haggag, an assistant professor at UCLA's Anderson School of Management, they wanted to make sure to adjust for variables that might explain slower wait times.

"We control for things like population, or population density, or the share of the population below the poverty line, and we still find that those disparities are incredibly robust," Haggag said.

Haggag also acknowledged that states may have different demographics or election systems.

"So then we look at, well, can we adjust for state effects and look within a state? And we still find a very similar racial disparity," he said.

Haggag said in Southern California, from Santa Barbara to San Diego, residents in Black neighborhoods waited about 45% longer than those in white neighborhoods - higher than the national number.

Within Los Angeles County, he said the disparity was a little lower than the national number - about 20%.

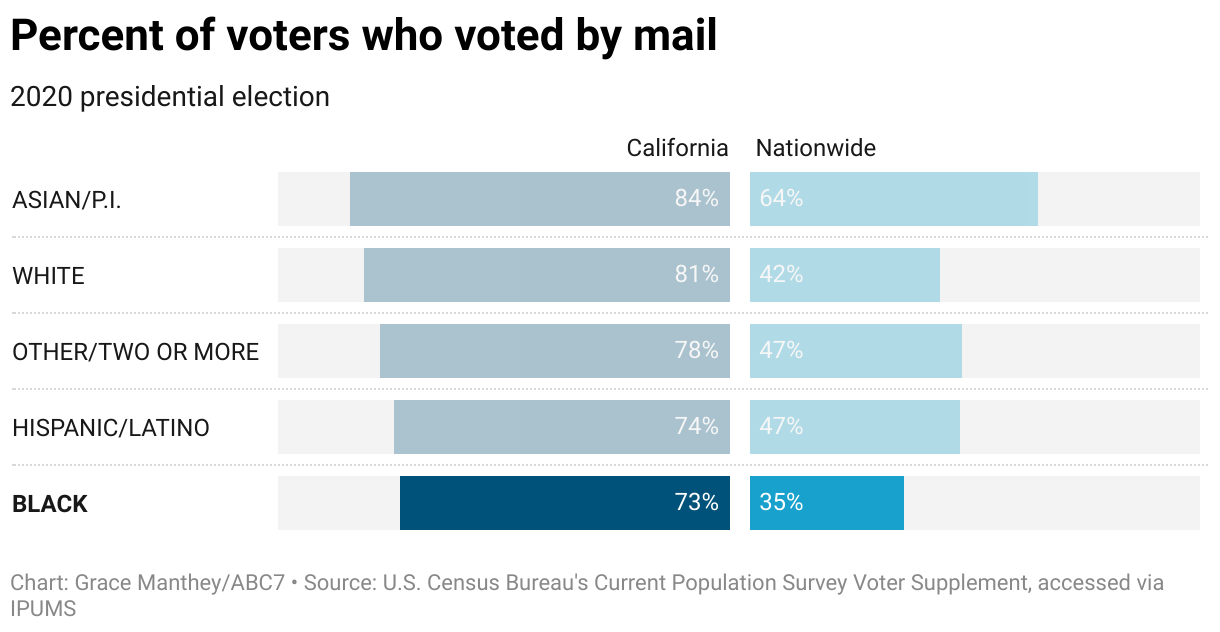

Voting by mail can help shorten long lines, but even with California's high rates of mail-in voting in 2020, Black voters were among those least likely to vote by mail.

Brown, from Black Voters Matter, said there's a sense of pride around voting in person.

"That was the one day that, literally, we could go in the booth and that our voice would be on par, that our voice would have the equal power as our white counterparts and other people in this nation," Brown said.

But Ray pointed out another reason: fear of their votes not counting.

"They wanted to actually see it go through the machine to ensure that their vote would count," he said.

Research from multiple states found evidence to support some of those fears.

An audit of 2020 voting data by the state of Washington found rejection rates are four times higher among Black voters than white voters. A study of 2018 Georgia mail-in voting data found that newly registered, young and minority voters had higher rejection rates than their counterparts. An ACLU report out of Florida found similar results.

"Systemic racism plays a role," Ray said. "From simple things such as people trying to say that people's signatures don't match up to people changing addresses and then having to go to two to three different places to try to get their addresses aligned with their voter card. These are all the things that are set up, oftentimes, to reduce voter turnout."

But barriers go beyond what Ray calls the "simple things." In most states, those serving a term in state or federal prison for the conviction of a felony cannot vote. In California, voting rights are restored once someone's term is up.

Still, Black Californians are three times more likely to be disenfranchised due to felony convictions, according to a 2020 report by the Sentencing Project.

"You put all these things together, you have people being less likely to be able to vote," Ray said.

"How many hoops are people going to have to jump through? And, depending on what state you live in, depending on your social class background and, unfortunately, depending on your race, you will have to jump through more hoops to try to vote than other people," Ray said.

Different sized gaps for different candidates

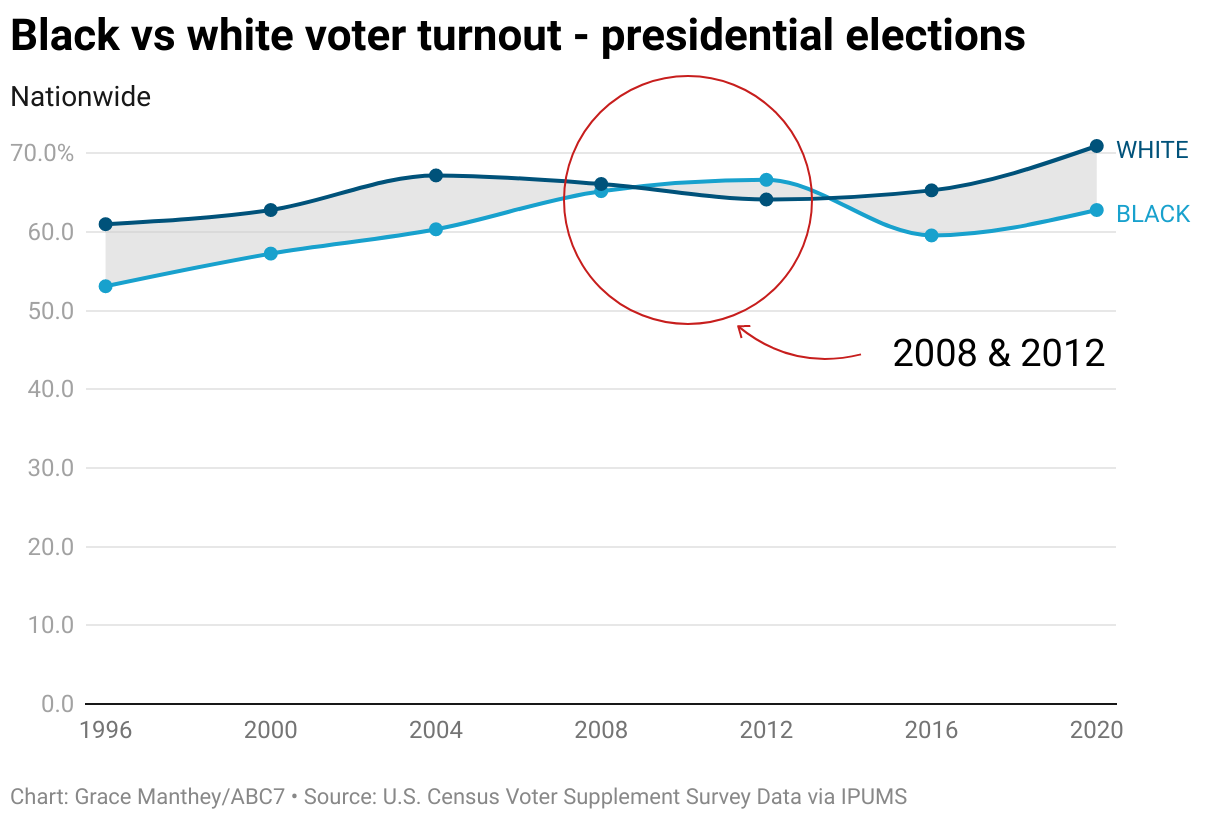

Nationwide gaps between Black and white voter turnout rates in presidential elections have been consistent since the late 1990s, except for the two elections in which President Barack Obama was elected.

"There was a candidate that energized the base, that Black people and Black voters in particular, saw a candidate that they identified with," said Brown.

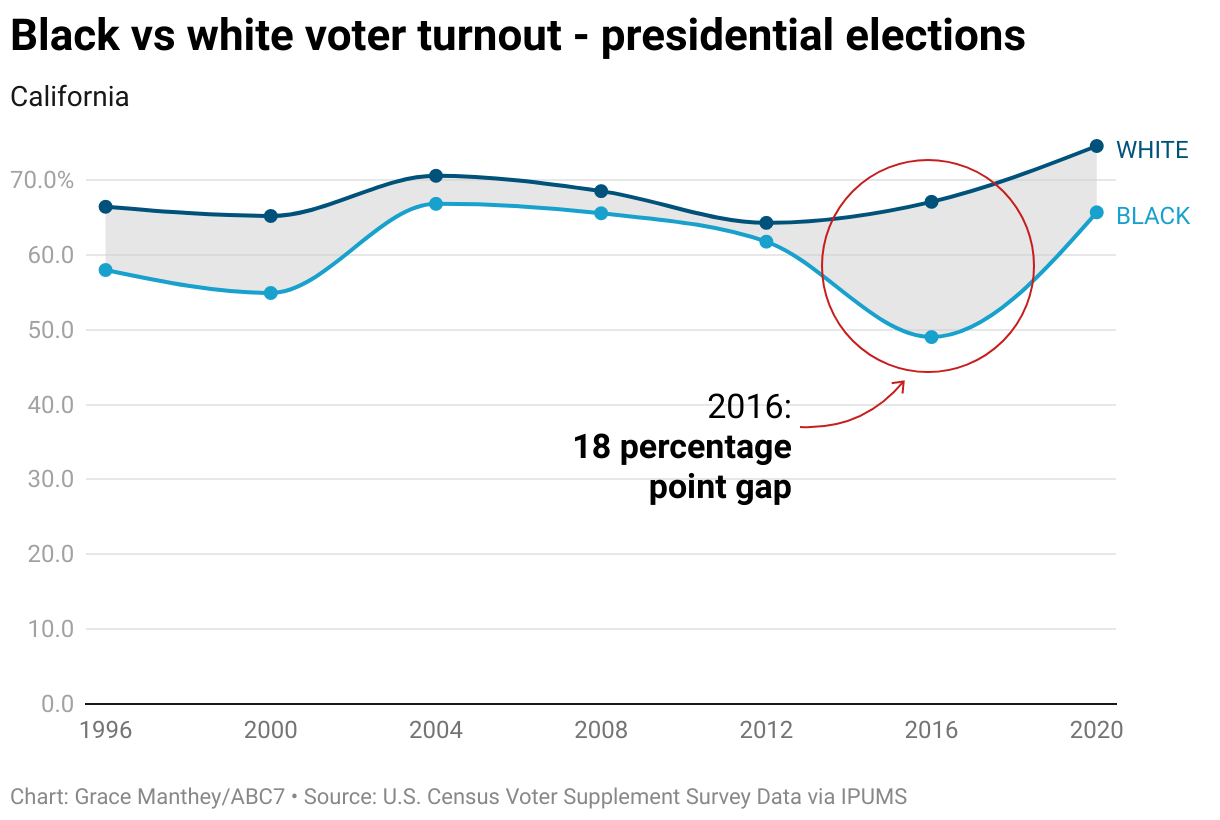

But the year President Donald Trump was elected, California saw its biggest gap between Black and white turnout in recent history.

According to Ray, there was a level of apathy around that election.

"In 2016, I think that it was so much going on, that people could not make heads or tails of it, and because people could not make heads or tails of it, they decided to stay at home," he said.

Ray also said he didn't think the candidates did enough to engage Black voters and to earn their votes. That backs up census survey data showing the most common reason survey respondents gave for not voting in the 2016 presidential election was not liking the candidates or issues.

Overcoming apathy: Messaging and accountability

Voting gaps and apathy issues are partly a result of messaging problems, according to Pastor William Smart Jr., the president and CEO of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference of Southern California.

Smart has worked with Democratic campaigns and faith-based voter outreach programs for decades and said candidates need to better engage with Black communities.

"You got to listen to this constituency and really begin to develop different policies that are going to affect their lives, I think a lot of times that has been missed," he said.

"We have to have the resources to knock on doors that are not being knocked on," Smart continued.

But experts said many can also develop voting apathy living in a gerrymandered district - when officials draw boundaries to favor a particular party or class.

"They're thinking about how their vote has been diluted down, or the way that it's been concentrated with other people who are simply going to vote exactly like them," said Ray.

Tappan Vickery, the director of voter engagement for Headcount, a nonprofit known for registering people to vote at concerts and festivals, mentioned the recent Supreme Court ruling on Alabama's recently redrawn districts.

Roughly 27% of Alabama's population is Black. But with the proposed maps, just one out of the state's seven districts would be majority Black. Lower courts blocked the maps, saying the state needed another majority Black district. The U.S. Supreme Court reinstated them for now.

"That doesn't really seem like a fair representation of the population there, and because of that, it is going to impact diversity in your elected officials," Vickery said.

She also encouraged people to pay attention to redistricting processes in their state and to make public comments if there is still an opportunity.

According to Ray, another effect of gerrymandering diluting the vote of some communities is that "the primaries become a big deal." But primary elections tend to have lower turnout than general elections.

"People take for granted that if a person is Republican or Democrat that they think the same. They don't. Because we have an overly simplistic two-party system, there's actually a lot of variation there," Ray said.

He also pointed out that it's important for voters to look beyond Capitol Hill, D.C. and Congress.

"There are local races for city council for other positions that matter a lot," he said. "With that being said, not only is it about the fact that people don't think their vote will matter, they also think that the people who they put in office are not doing enough."

According to Smart, holding those people in office accountable is key to keeping voters engaged beyond the election.

"We have to force elected officials to come up with the policies that are going to affect our lives in a very positive way," Smart said.

"If the elected official can't do it, we vote someone in that can," he continued.

He said there's no more room for elected officials getting into office and then giving excuses for not being able to fulfill promises.

"That day's over," Smart said over a Zoom call, shaking his head.

Brown echoed Smart's sentiment and said the most sustainable way to increase turnout is to move away from voting "episodically," and then letting leaders just take over.

"For people to really start connecting voting to their own power, that's where we've seen the biggest change," Brown said.

How should community members voice their comments and concerns? Smart said the way they always have.

"We call them, we write them, email, and we show up on these Zooms now, and you know, that still moves people," said Smart.