'Every second counts:' LAFD chief aims to tackle increased response times, staffing shortages

In January of this year, the average response time was more than 7 minutes.

LOS ANGELES (KABC) -- The Los Angeles Fire Department is busier than ever.

There was the COVID-19 pandemic, then add to that the homeless crisis, the rise in fentanyl overdoses and an uptick in violent crime.

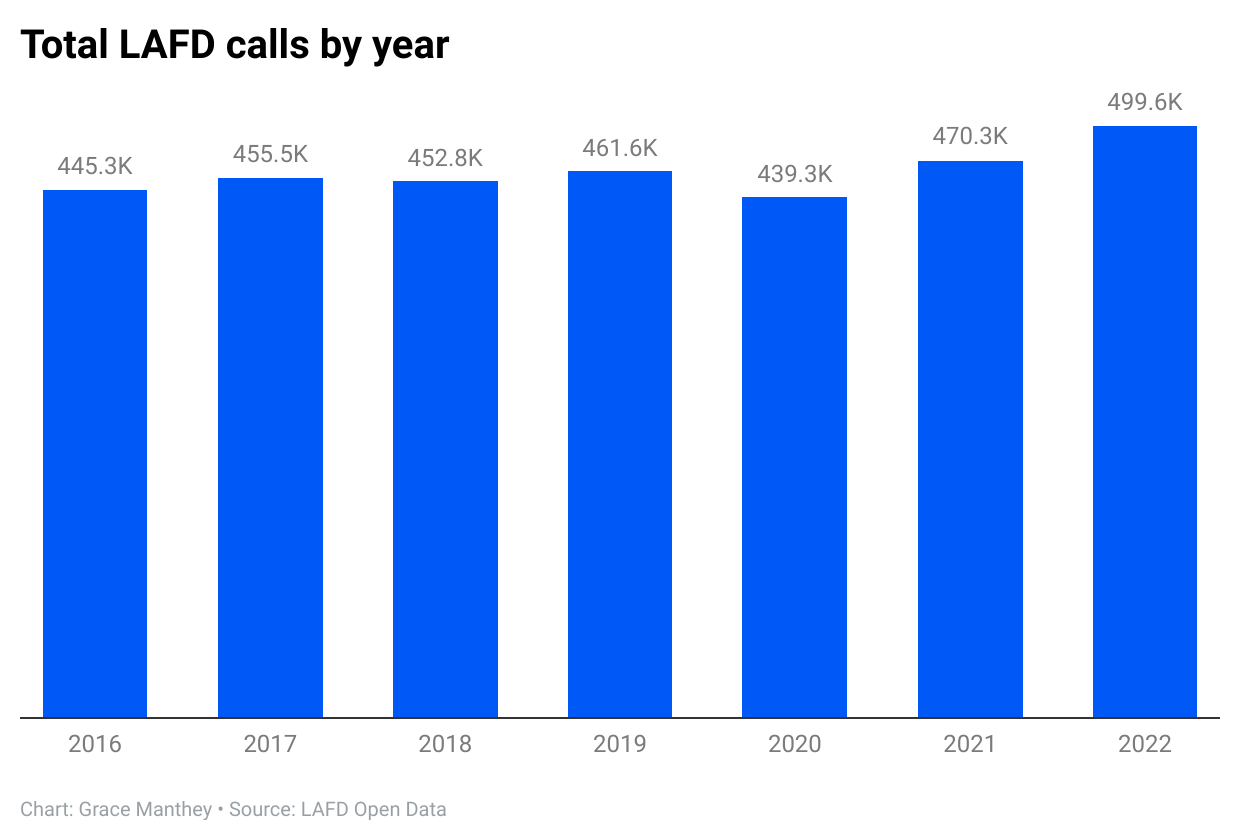

Last year, the LAFD responded to nearly 500,000 incidents, 46,000 more incidents than the average between 2016 and 2019 prior to the pandemic - which is about 10% higher.

"We are over worked," said LAFD paramedic Jonathan Valenzuela.

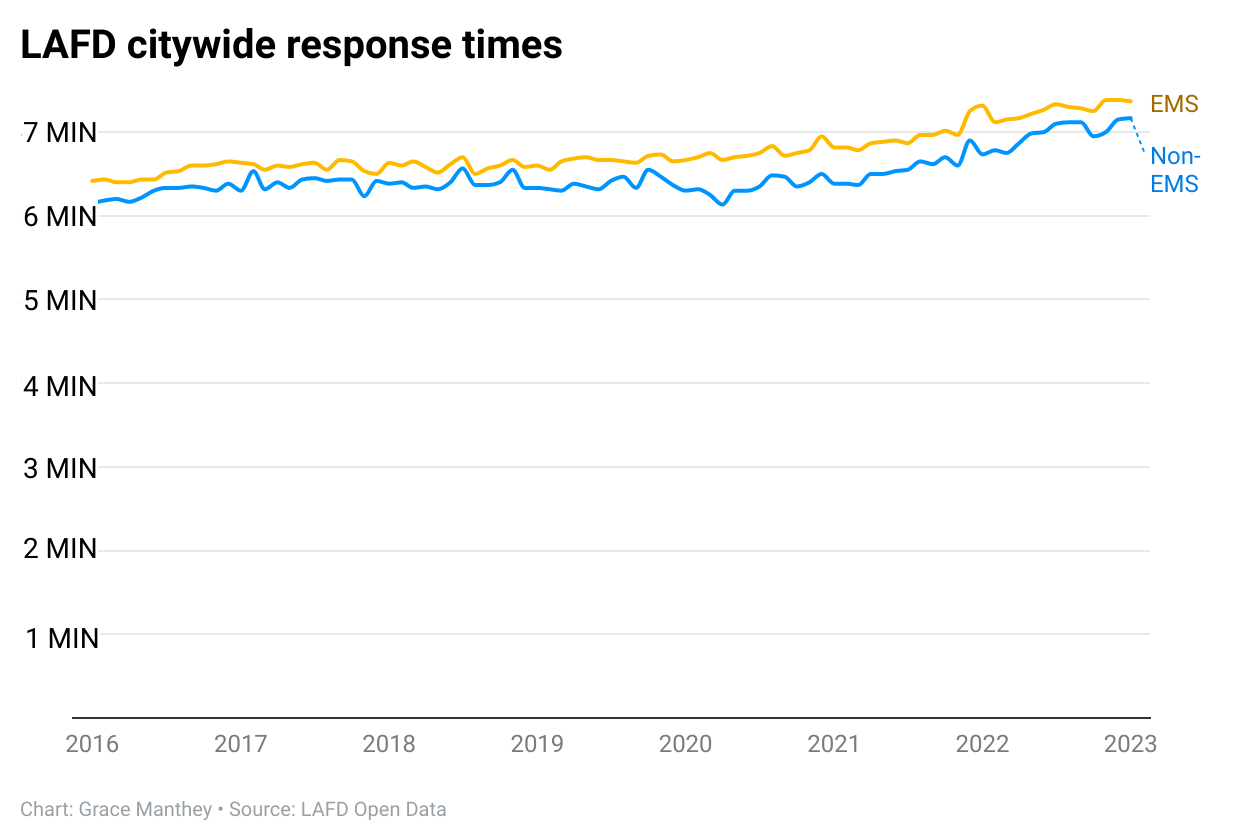

As a result of the call volume, LAFD response times have increased citywide. EMS and non-EMS responders both took a minute longer in January 2023 compared to January 2016.

In January of this year, the average response time was more than 7 minutes.

"Every second counts when it comes to the services we provide," said LAFD Chief Kristen Crowley. "With an increase in response times, absolutely we're paying close attention to that. But that's the cycles we're talking about. An increase in workload, but not an increase in staffing."

That's why Crowley, who will mark one year on the job later this month, recently met with Los Angeles Mayor Karen Bass to ask the city to fund an additional five fire academies on top of the existing five, giving the department 300 additional personnel.

"Our members who are about to retire, they are towards the end of their career. So there may be issues with muscular skeletal issues," said Crowley. "So, they're off, long-term. So those are vacant positions that we need to fill. Our firefighter paramedics sworn members are the ones filling those positions, sacrificing time away from their friends and family for many days in a row."

This week, Eyewitness News interviewed Bass and asked her how she plans to address LAFD's response times.

"I relied on paramedics during the time my mother was ill and they saved her life numerous times," said Bass. "If they were late, she might not have survived. So yes, I feel very strongly about that, but my commitment is to help them reach the capacity so that their times are shortened."

However, there are other issues facing the department.

The increase in calls has taken a toll on the mental health of firefighters and paramedics, who rarely have a break from the intense workload.

Crowley said getting the men and women of her department to ask for help is a challenge.

"You asked what keeps me up at night, I want to make sure we take care of our firefighters when it comes to their overall health, safety and wellbeing," she said. "Shattering that stigma that it's ok to ask for help. Most of our firefighters think, 'Eh,' but the question is who rescues the rescuers? Our behavioral health program, we have a number of fire psychologists already in place."

Valenzuela has been with the department for 14 years.

He's currently a part of a specialized fast response paramedic unit assigned to Skid Row that doesn't transport patients, but rather makes the decision whether to escalate or de-escalate a call, a better use of the department's resources.

"The problem still I see is the inundation of calls of 911 responses that are not 911," he said. "There needs to be more public education on what a true emergency is so that we can provide that level of service that the public expects."

Valenzuela says the public can also help the department reduce the 911 call volume.

"We got sent out to somebody that was having toe pain. We arrived on scene and it was us and EMT ambulance. We arrived and we were able to determine that all they needed was verbal guidance to the local urgent care center," said Valenzuela.

A major focus for Crowley, besides staffing up and addressing the mental health of her firefighters, is improving resource deployment.

Instead of sending an engine and an ambulance to every call, saving those resources for when they are needed the most so they can get to the call as fast as possible.

Grace Manthey contributed to this story.